The stability of a key Antarctic glacier appears to have taken a turn for the worse as a large iceberg that broke off during September has swiftly shattered. Meanwhile, scientists are concerned that the rate of sea level rise could further accelerate in a world forced to rapidly warm by human fossil fuel burning.

(Iceberg drifting away from the Pine Island Glacier rapidly shatters. Image source: European Space Agency.)

This week, a large iceberg that recently calved from West Antarctica’s Pine Island Glacier rapidly and unexpectedly disintegrated as it drifted away from the frozen continent. The iceberg, which covers 103 square miles, was predicted to drift out into the Southern Ocean before breaking up. But just a little more than two months after calving in September, the massive chunk of ice is already falling apart.

The break-off and disintegration of this large berg has caused Pine Island Glacier’s ice front to significantly retreat. From 1947 up until about 2015, the glacier’s leading edge had remained relatively stable despite significant thinning as warmer water began to cut beneath it. But since 2015, this key West Antarctic glacier has begun to rapidly withdraw. And it now dumps 45 billion tons of ice into the world ocean each year.

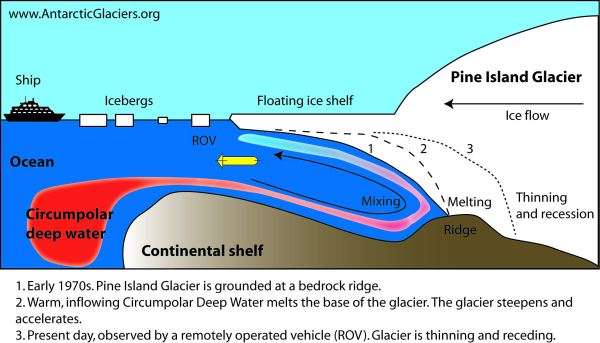

(Glaciers like Pine Island balance on a geological razor’s edge. Because they sit on a reverse slope, it only takes a relatively moderate amount of ocean warming to precipitate a rapid collapse. These collapses have happened numerous times in the past when the Earth warmed. Now, human-forced climate change is driving a similar process that is threatening the world’s coastal cities. Image source: Antarctic Glaciers.)

The present rate of melt is enough to raise sea levels by around 1 millimeter per year. That’s not too alarming. But there’s concern that Pine Island Glacier will speed up, dump more ice into the ocean and lift seas by a faster and faster rate.

Pine Island Glacier and its sister glacier Thwaites together contain enough water to raise seas by around 3-7 feet. The glacier sits on a reverse slope that allows more water to flood inland, exposing higher and less stable ice cliffs as the glacier melts inland. If the glacier melts too far back and the ice cliffs grow too high, they could rapidly collapse — spilling a very large volume of ice into the ocean over a rather brief period of time. As a result, scientists are very concerned that Pine Island could swiftly destabilize and push the world’s oceans significantly higher during the coming years and decades.

No one is presently predicting an immediate catastrophe coming from the melt of glaciers like Pine Island. However, though seemingly stable and slow moving, glacial stability can change quite rapidly. Already, sea level rise due to melt from places like Greenland and Antarctica is threatening many low-lying communities and nations around the world. So the issue is one of present and growing crisis. And there is very real risk that the next few decades could see considerable further acceleration of Antarctica’s glaciers as a result of human-forced warming due to fossil fuel burning.

Dr Robert Larter, a marine geophysicist at British Antarctic Survey, who has researched Pine Island Glacier in his work with the Alfred Wegener Institute, recently noted to Phys.org:

“If the ice shelf continues to thin and the ice front continues to retreat, its buttressing effect on PIG will diminish, which is likely to lead to further dynamic thinning and retreat of the glacier. PIG already makes the largest contribution to sea-level rise of any single Antarctic glacier and the fact that its bed increases in depth upstream for more than 200 km means there is the possibility of runway retreat that would result in an even bigger contribution to sea level.”

CREDITS:

Hat tip to Colorado Bob

Hat tip to Erik Friedrickson