“The message we are getting is if we don’t take care of nature, it will take care of us.” — Elizabeth Maruma Mrema, Acting UN Executive Secretary on the Convention on Biological Diversity.

“It boggles my mind how, when we have so many diseases that emanate out of that unusual human-animal interface, that we don’t just shut it down. I don’t know what else has to happen to get us to appreciate that.” — Dr. Anthony Fauci on live animal markets, aka wet markets, in Asia and elsewhere.

“The term wet market is often used to signify a live animal market that slaughters animals upon customer purchase.” — X. F. Xan

“This is a serious animal welfare problem, by any measure. But it is also an extremely serious public health concern.” — Kitty Block, President and CEO of the Humane Society of the United States.

*****

As we come closer to the present time, to the present COVID-19 Climate of Pandemic, we run into illnesses that are more mysterious. HIV, for example, has been the object of intense investigation and scrutiny for many decades now. So the level of knowledge about how HIV emerged is quite rich. Less so with Ebola, but that infection is still moderately well understood.

SARS — Another Novel Illness

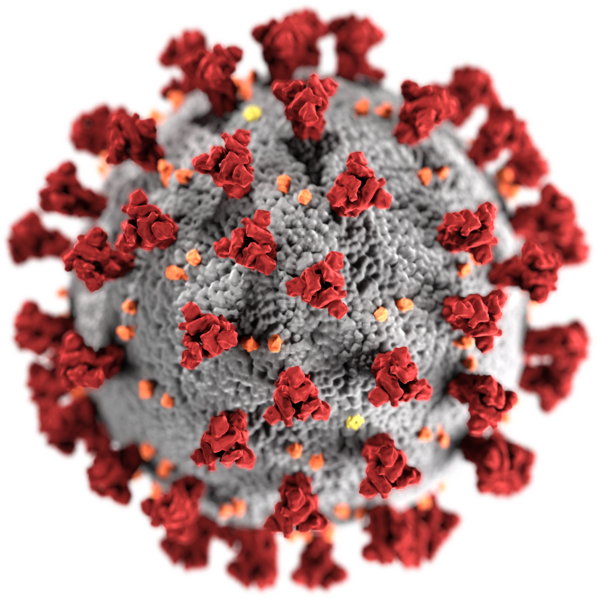

With the newer SARS illness — short for severe acute respiratory syndrome, the well of scientific understanding from which we can draw is far more shallow. But it is certainly relevant. For the present global pandemic which now has paralyzed our entire civilization and which threatens to take so many of our lives resulted from the second strain of human SARS to emerge in our world.

What we do know is that the SARS virus is another new zoonotic illness. The first strain of SARS broke out in a 2002 epidemic in China that then rapidly spread. It emerged from a family of coronaviruses. A set of viruses that typically cause mild respiratory infections in humans. But SARS virus is not mild. It is quite often severe — resulting in hospitalization in a high proportion of cases. It also shows a much higher lethality rate than typical illness.

SARS comes from a lineage, like HIV and Ebola, that had previously thrived in the hotter regions of the globe. It was harbored in tropical and subtropical animal reservoirs. It emerged at a time when animal sicknesses were likely amplified by direct environmental stresses caused by forest clear cutting, human encroachment, and the broader sting inflicted by the climate crisis. The novel awakening of SARS was, finally, yet another case where harmful contact with sick animals resulted in a transfer of a new illness to human beings.

Coronaviruses in Hot-Bodied Bats in a Hot Weather Region

The first strain of human SARS illness was genetically traced back to a coronavirus ancestor in horseshoe bats — a tropical and subtropical bat species — in 2002 by Chinese researchers. Like the Ebola Virus and HIV before it, SARS-like illness circulated through various species in tropical and sub-tropical environments in a traditional reservoir long before transferring to human beings.

The primary range of horseshoe bats is paleo-tropical. Horseshoe bats, according to genetic research, are an animal reservoir of SARS virus. Image source: Paleo-tropical environment.

Studies note that bats are a reservoir for a great diversity of coronaviruses. The bat anatomy is a warm one in a hot weather environment — subject to constant exercise and exertion in regions where it’s not easy to cool off. Elevated body temperature is a traditional mechanism for fighting infection. So these viruses have to constantly adapt and mutate to keep hold in the bat population.

At some point, one particular strain of coronavirus jumped out of the bat population and into another animal species. A paper in the Journal of Virology suggests that the genetic split from bat cornaviruses and SARS occurred some time around 1986 or 17 years before the 2002-2003 outbreak. At that time, it is thought that this hot weather illness from hot-bodied bats had moved to another, intermediary, animal host.

SARS in the Little Tree Cats — Palm Civets

The first emergence of SARS is thought to have occurred when palm civets — a kind of Southeast Asian tree cat — consumed coronavirus inflected horseshoe bats. The civets typically dine on tree fruits. But as omnivorous creatures they also eat small mammals. In this case, civets are thought to have eaten sick bats and become sick themselves.

- The Palm Civet of Southeast Asia — hunted as bush meat for the Asian wet markets. A practice suspected for transferring SARS from bats to humans. Image source: Black Pearl, Commons.

Palm civets live throughout much Southeast Asia. Inhabiting a swath from India eastward through Thailand and Vietnam, running over to the Philippines and southward into Indonesia. A tree-dwelling creature, they prefer primary forest jungle habitats. But they are also found in secondary forests, selectively logged forests, and even parks and suburban gardens. All of which overlap the environment of horseshoe bats and their related coronavirus reservoir.

The leap from bats to civets and its development into SARS probably didn’t occur suddenly. Many civets probably consumed many sick bats over a long period of time before the coronavirus changed enough to establish itself. But at some point in the 1980s, this probably occurred.

From that point it took about 17 years for the virus to make its first leap into humans. How the virus likely made this move is eerily familiar — taking a similar route to the devastating HIV and Ebola illnesses.

Wet Markets — Butcheries For Asian Bush Meat

A major suspect for the source of this particularly harmful contact is the Chinese wet market system. A wet market is little more than a trading area that contains, among other things, live and often exotic animals for sale as food. A person entering a wet market is confronted with thousands confined live animals. They can point to a particular animal and a wet market worker will butcher the creature on the spot.

It’s literally a very bloody business. The butchering occurs in open air. Blood and body fluids can and often do splatter anywhere. As a result, the floors are typically wet from continuous drippage and, usually partial, cleaning — which is how the market derives its name.

Palm civets can often be found in wet markets as food in China. Trappers for the wet markets range the Southeast Asian jungles bringing in civets by the thousands. The civets were reservoirs for SARS virus. They were slaughtered in the messy markets. People were exposed. In 2002 and in 2019 they got sick.

Though palm civets have been identified by many avenues of research as a likely source of SARS, raccoon-dogs — whose meat was sold in wet markets — were also shown to be SARS type virus carriers. These animals have a similar diet to that of civets, share their habitat and were similarly vulnerable to infection from the bats. In addition, pangolins — a kind of scaly anteater — have been identified as a possible carrier of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. And pangolin meat is also sold for consumption in Vietnam and China.

Given our knowledge of how zoonotic illnesses move in animal populations, it’s possible that multiple species are involved in the ecology of SARS and related coronaviruses. In essence, there is a strange and ominous similarity between wet markets in Asia and the bush meat trade in Africa. They are both means of moving jungle meats from animals (who may be reservoirs for novel illnesses) in tropical regions into the human population. Often in a fashion in which the treatment and preparation of the meats to be consumed is haphazard and unregulated.

First SARS Outbreak — 2002-2003

Ultimately, the disease percolating through likely stressed natural systems found its way into the human population in late 2002. The epicenter was Guangdong Province in China where the highest proportion of early SARS cases by a significant margin (39 percent) showed up in people in the live animal food trade. In other words, people who butchered animals or worked closely with those who butchered animals.

The initial infections, which were traced back to November in China, resulted in spikes of pneumonia incidents in local hospitals. The cause — a then unknown illness that was later called SARS. SARS was another terrifying illnesses. Its symptoms could emerge rapidly or slowly over a couple of days or weeks. It could mimic flu-like symptoms before suddenly surging into a terribly lethal illness that attacked the lungs — rendering victims unable to breathe under their own power. At first, case fatality rates (the percentage of people who died as a result of SARS) ranged from 0-50 percent. The ultimate recorded fatality rate from the initial outbreak in 2002 would settle at 9.6 percent or about 100 times more lethal than seasonal flu.

Cumulative reported SARS-CoV cases during the 2002-2003 outbreak. Note that early case reporting was incomplete. Image source: Phoenix7777 and WHO.

From the point of early infections, patients then passed on the virus to healthcare workers and others. Though SARS was not as crazy lethal as HIV and Ebola on an individual basis, it was quite infectious. Meaning it was much easier to pass on to others than either of those earlier emerging zoonotic illnesses. This higher transmission rate resulted in a greater risk that more people would fall ill from SARS over a shorter period of time — exponentially multiplying the virus’s lethal potential.

Transmission to workers in hospitals and care facilities was notable as typical sanitation procedures were not enough to limit virus spread. In hospital settings, the transmission rate for this first SARS illness (the number of people each infected person then got sick) was between 2.2 and 3.7. Outside of sanitized settings, the transmission rate ranged from 2.4 to 31.3. A particularly highly infectious patient, called a super-spreader, resulted in a mass spread of illness to workers at Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital in Guangzhou during January of 2003 and subsequently to other parts of China’s hospital system. Masks and protective gowns (PPE) were ultimately shown as necessary to contain SARS infection in hospitals.

China’s early failures to report on the 2002 SARS outbreak resulted in a somewhat delayed international response. But by early 2003, the World Health Organization was issuing warnings, advisories and guidance. Disease prevention agencies within countries issued their own responses including diligent contact tracing and isolation protocols. The containment response both within and outside of China was thus in full swing by early 2003. This action likely prevented a much broader pandemic. That said, a total of 8,096 cases were reported — 5,327 inside China and 2,769 in other countries. With the vast majority of cases occurring in China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Canada, Singapore and Vietnam. In total, out of the 8,096 people reported infected during this first SARS outbreak, 774 or 9.6 percent, perished.

SARS-CoV-2 Tsunami on the Way

Unfortunately, infectious diseases show no mercy to fatigued and degraded infectious disease responses. They lurk. They mutate. In their own way, they probe our defenses. They are capable of breaking out to greater ranges when diligence, ability, or will to protect human life wanes among leaders. And a smattering of SARS cases reported during the 2000s following the 2002-2003 outbreak continued as a reminder of its potential. So as with HIV and Ebola, we face waves of illness with SARS. With the next outbreak resulting in a global pandemic that will likely infect millions and kill tens to hundreds of thousands during 2019-2020.

Up Next: COVID-19 First Outbreak — Viral Glass-Like Nodules in Lungs