Storm surge poles are visible across the Outer Banks. These sentinels warn of potential flooding from powerful cyclones. Warming oceans and sea level rise make such flooding more likely.

All posts in category Climate Crisis

Friday For Future — Sea Level Rise, Storm Surge Poles, More Intense Cyclones

Posted by robertscribbler on January 14, 2023

https://robertscribbler.wordpress.com/2023/01/14/friday-for-future-sea-level-rise-storm-surge-poles-more-intense-cyclones/

Big Waves off Ireland, UK as Series of Storms Gather in the North Atlantic

Significant wave heights are in the range of 25-30 feet off Ireland as a progression of storms focuses on both Ireland and the UK over the next five days.

Posted by robertscribbler on January 7, 2023

https://robertscribbler.wordpress.com/2023/01/07/big-waves-off-ireland-uk-as-series-of-storms-gather-in-the-north-atlantic/

No COVID-19 Didn’t Stop the Climate Crisis, But It’s Interacting with it in a Bad Way

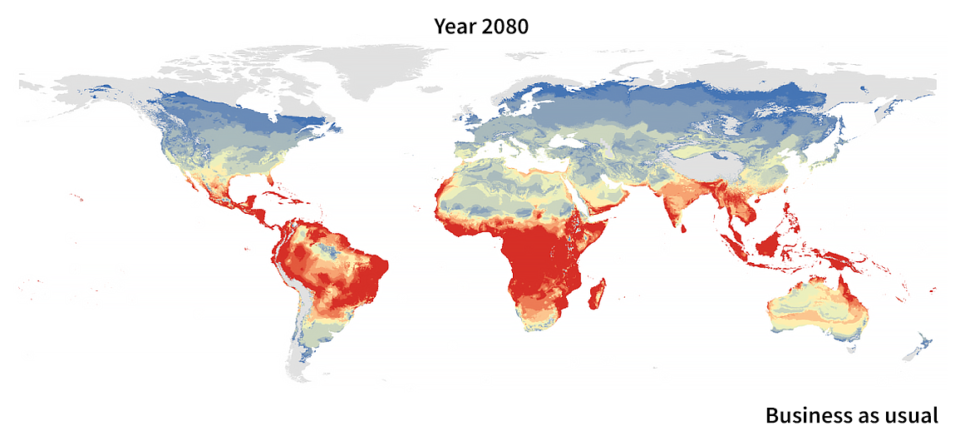

As we stand in the grips of one major global crisis, one whose first wave of mass casualties may finally be starting a merciful down-slope (on April 27, 2020), it’s important not to lose sight of the other, larger, one. Yes, I’m talking about the Climate Crisis. And as I mention it, I would be remiss to fail to note that one is not like the other. In particular, the climate crisis is much worse when measured over longer time scales and taken in total.

In an April 21 address ahead of Earth Day, U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres stated:

“Currently, all eyes are on the COVID-19 pandemic, the biggest test the world has faced since the Second World War. We must work together to save lives, ease suffering, lessen the shattering economic and social consequences, and bring the disease under control. But, at the same time, let us not lose focus on climate change. The social and economic devastation caused by climate disruption will be many times greater than the current pandemic.”

The reason is that the climate crisis is on a path of escalating damage and danger so long as we continue burning fossil fuels. One that does not relent if the carbon emission itself does not permanently abate. One that in the broader sense is capable of spinning off multiple sub-crises or harmfully amplifying and influencing others. Or in a sense that is in a micro-way more specific to the present pandemic, as we touched on early in this web-book, climate crisis can help to worsen and spread new infectious diseases.

COVID-19, Air Pollution, Deforestation, Warm Weather Illnesses, and Health Systems Impacted by the Climate Crisis

In the context of the present COVID-19 pandemic, the climate crisis, and its driver (fossil fuel based pollution), produces a number of harmful infectious illness interactions that are worth pointing out. Namely, the air pollution that drives the climate crisis can increase the death rate from COVID-19, the deforestation that also helps to drive the climate crisis can serve as a driver for the emergence of new coronavirus based illnesses like COVID-19, that COVID-19, like Ebola is a novel infectious illness from a typically warmer weather region, and that the climate crisis has deleterious impacts on the global health system that challenges our ability to manage such a wide-ranging pandemic outbreak. As we’ll glimpse below, COVID-19’s interaction with climate change denial and its related anti-science bent, has also been particularly harmful.

Second Hottest January through March on Record for 2020

A larger update for the climate crisis, however, takes in a couple of basic data points that show we are still on a very damaging and destructive climate pathway. One that the COVID-19 based economic slowdown and related temporary reductions of emissions by itself cannot halt (more on this later). A path we won’t effectively depart from unless we exit the COVID-19 pandemic by enabling a rapid transition to clean energy and a related follow-on effort to draw down excess atmospheric carbon.

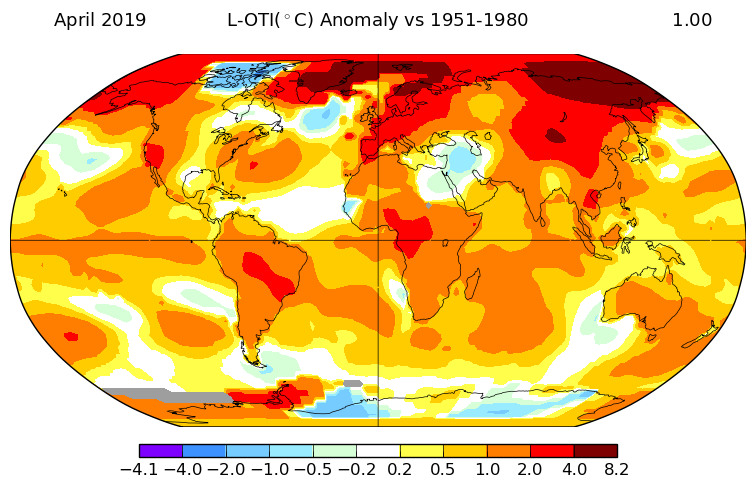

First quarter of 2020 was the second hottest on record according to NASA GISS. Image source: NASA.

The first key climate crisis data point we’ll explore in this installment is provided by the climate experts at NASA GISS, headed by Dr Gavin Schmidt. And it comes in the form of a global surface temperature analysis for the first quarter of 2020. For, according to NASA, during the months of January through March of 2020 global surface temperatures averaged about 1.19 degrees Celsius above 20th Century baseline measures. This is about a 1.41 degree Celsius departure above 1880s averages. Quite a bit higher than the past five year baseline at 1.15 C hotter than 1880s averages and just 0.06 C below the record hot first quarter of 2016. It is also disturbingly close to the IPCC identified first climate threshold mark at 1.5 C. A threshold which we are probably still about a decade and a half away from breaching over a five year average time-frame along the present fossil fuel burning pathway. But it’s still not fun seeing us so close to it at present.

With such an opener, 2020 may not become a new record hot year. Somewhat less likely given no El Nino is expected, but possible. And if it does, it would spell more trouble. We’ll wait for confirmation on the 2020 temperature trend coming from NASA GISS and Dr Gavin Schmidt — who has dutifully provided publicly helpful annual temperature path projections during recent years. Regardless, 2020 will likely come uncomfortably close to another record hot year. And such continuing severe global heat is certainly within a well-established trend of longer-term heating.

Atmosphere Still Filling up with Carbon

Of course the primary driver of climate crisis is fossil fuel burning and related emissions of greenhouse gasses into the Earth’s atmosphere. Emissions that have temporarily slowed down — possibly by as much as 5-10 percent for 2020 according to this report by Carbon Brief — but have not halted. And emissions would have to slow down by a lot more and for a lot longer to start having a positive impact on the Earth’s climate system.

According to Glen Peters, research director at CICERO: “Even if there is a slight decrease in global fossil CO₂ emissions in 2020, the atmospheric concentration of CO₂ will continue to rise. The atmosphere is like a (leaky) bathtub, unless you turn the tap off, the bath will keep filling up with CO₂.” A statement of basic facts that climate change deniers who attack science are even now trying to confuse (see this scientist’s statement to clarify).

Not only are top voices at CICERO chiming in on the issue of climate crisis and a COVID-19 related temporary economic slow-down. But recently the World Meteorological Organization issued its own statement on the matter noting — the economic and industrial downturn as a result of the Coronavirus pandemic is not a substitute for concerted and coordinated climate action.

Climate Science Deniers Continue to Publicly Demonstrate a Dangerous Incompetence on COVID-19

We could give flight to reason and join in the ranks of science deniers who ignore and refute experts at places like CICERO and the World Meteorological Organization. Basically the same set of people who downplay or attack the advice of experts (like those at the World Health Organization) and ignore facts at our own and everyone else’s peril (but we won’t). We could listen to people like the current occupant of the White House (but we don’t). A known climate science denier who’s also spent months attacking public health experts and defunding key disease fighting groups while also peddling questionable COVID-19 treatments like hydroxychloroquine of unproved, potentially harmful, effectiveness. Who on Thursday, April 23rd appeared to publicly suggest injecting disinfectants (like Windex and Bleach) into our bodies as a valid way to fight COVID-19 infection (Do not do this! It can kill you!).

Trump later walked his ridiculous and dangerous statements back, while blaming his usual scape-goat — the free press — for his own brazen incompetence. But his most recent fact-free and literally dangerous circus show again put public health at risk with the potential to drive some of those who take his statements verbatim to inflict harm upon themselves. It also precipitated public health advisories from officials and the makers of Bleach and Windex advising people to, well, not take the President’s apparent advice. We could put ourselves at further risk by listening to his quackery-defending supporters, now lifting up a familiar gas-lighter chorus to try to tell us what we all saw happen didn’t, and related cohorts. But this form of self-harm follower-ship, or of even entertaining it, is proving to be a very, very bad idea. For the tendency here to deny the science on one threat — COVID-19, that those clinging to a certain political ideology are incapable of managing responsibly — is apparently related to their inability to perceive the larger threat of climate crisis.

CO2 Strikes Above 416 Parts Per Million During April of 2020

So instead we will just do the smart, rational thing and listen to the actual experts (I know many of us already do, but unfortunately and increasingly obviously some still do not) — world-class scientists who have spent their lives researching the Earth’s climate system. Scientists like Dr Michael E Mann, Dr Katherine Hayhoe, Dr Terry Hughes, Dr Stefan Rahmstorf, Dr Peter Gleick, Dr Gavin Schmidt, Dr Eric Rignot and so many more. And the atmospheric greenhouse gas indicators for the climate crisis that these scientists follow are still heading in the wrong direction. Still building up. Still providing more heat trapping capacity for the Earth’s atmosphere and larger climate system.

The seasonal carbon dioxide trend for the past two years as measured at the Mauna Loa Observatory shows continuing increases driven by fossil fuel burning. Image source: The Keeling Curve.

At this time, atmospheric CO2 is hitting above a 416 parts per million average on a weekly basis. This is well above anything seen in at least the last 2.6 to 5.3 million years and likely since the Middle Miocene 15-17 million years ago. According to the real experts at NOAA, this greenhouse gas is the primary driver of the present Earth System heating we now observe (see the Earth Systems Research Lab’s Greenhouse Gas Index Page).

So both heat and its big driver CO2 are still heading in the wrong direction. And, no, the fossil fuel burning tap into the tub didn’t stop running, it just turned down a bit. Hopefully permanently — but that will depend on what kind of economic stimulus we provide to help get us out of this crisis. Particularly for what kinds of energy systems we decide to stimulate to help get the global economy back up and running (clean energy to help stop the climate crisis and business as usual fossil fuel burning to keep making it worse) when the COVID-19 pandemic ultimately abates.

Up next: Social Distancing and Waiting Until It’s Safe Enough to Re-Open

Posted by robertscribbler on April 27, 2020

https://robertscribbler.wordpress.com/2020/04/27/no-covid-19-didnt-stop-the-climate-crisis-but-its-interacting-with-it-in-a-bad-way/

The Trouble With Testing Part 1 — “No Responsibility at All”

“The White House is now home to an inattentive, conspiracy-minded president. We should not underestimate what that could mean.” — The Atlantic in a special report on U.S. pandemic preparedness during the July/August 2018 issue.

“Anybody that wants a test can get a test. That’s what the bottom line is… and the tests are all perfect, like the letter was perfect. The transcription was perfect, right?” — Donald Trump on March 6 as U.S. was suffering a major shortage of COVID-19 test kits.

“I take no responsibility at all.” — Donald Trump when asked if he felt any responsibility for the persistent lags in U.S. testing capability on March 13.

“President Trump continues to falsely state that everyone who needs a COVID-19 test can get one.” — In an NPR interview conducted on April 2.

“Two and a half months after the first reported coronavirus case in the US, America still doesn’t have the capacity that it needs to track all cases…” — Vox.

*****

The need for testing during a virus epidemic is directly related to the number of infected persons. If the outbreak is small, the need for testing is also proportionately smaller. And if the outbreak is large, then the need for testing is subsequently much larger.

Ironically, the more testing happens early on, the more cases are identified early on, the more contacts are traced and isolated early on, the more the virus is ultimately contained and the lower the follow-on need for tests. The inverse is also true. The less testing, identifying, and containing of pandemic illness early on, the more tests will later be needed.

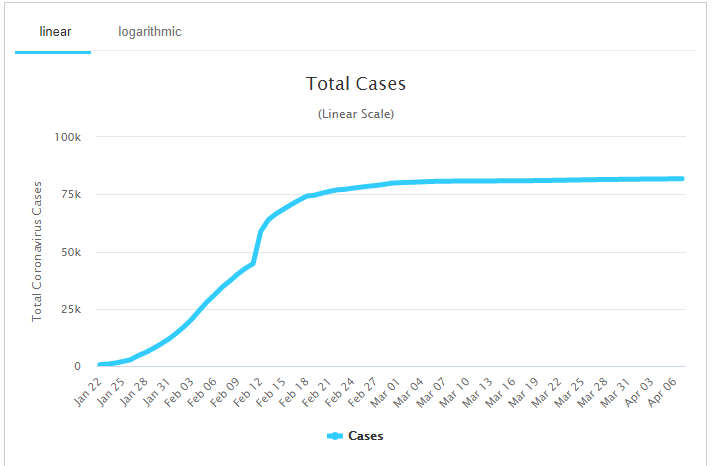

A failure to test, trace and isolate in the U.S. early on resulted in a massive COVID-19 outbreak necessitating nationwide mitigation. 1 in 5 people tested in the U.S. are still showing up as positive as of April 20th — indicating that tests are generally still occurring only for high risk persons and not for the broader population. Image source: Our World in Data.

Because less testing, identification and containment means an illness like COVID-19 can expand undetected, exponentially, and with far less constraint. Each failure to respond to this nasty disease pushes us up the scale in the need for a still greater response in the form of testing, isolation, sanitation, and ultimately mitigation. And if leadership is incapable of providing that response in a continuous escalation, then we end up with an ever-expanding disaster. That’s what we face here in the U.S. Because here a national leadership under Trump that utterly lacks responsibility is showing its dramatic incapacity.

A Question of Responsibility

What is responsibility? At its root — response. In a disaster, swift, decisive, and effective response is what it takes to prevent an expanding and uncontainable cascade of harm, economic loss, and loss of life. Without leadership responsibility, a sense of duty to the persons under leadership’s charge and a willingness to answer to others, to positively absorb criticism, to act, to overcome barriers in order to make effective action possible, then crisis and disaster response itself will be set up to fail.

In the context of COVID-19, U.S. leadership failure by a corrupt and incompetent Trump Administration has weighed heavily in loss of life and well-being. Specifically, the Administration’s failure to take the responsibility necessary to provide the tests Americans need has been a critical aspect of this failure.

Test Development Timeline in a Global Context

Unlike South Korea which took swift action and outran global COVID-19 testing capability, the U.S. response under Trump in the form of deploying viable test kits, has lagged it.

On December 30 and 31 of 2019, China and WHO had identified pnemonia-like cases of a new illness. By January 10-12 of 2020, China released the new disease (later called SARS-CoV-2 for the virus or COVID-19 for the illness the virus causes) genome to the world. Within just a few days, German scientists, using SARS-CoV as a reference, had developed a test that could identify a unique portion of the SARS-CoV-2 virus’s DNA. On January 17, the World Health Organization (WHO) adopted the German-based test, published the guidelines for developing the test, and began working with private companies to rapidly produce those tests and distribute them. As other agencies developed new tests, WHO would also publicly provide the new formulas. For example, WHO published China’s test development formula one week later on January 24.

The importance of WHO action at this stage was threefold. First, it provided information on how to manufacture an effective test. In other words, any country could take the WHO-provided information and use it to mass produce its own tests. Like South Korea, they could then independently coordinate with medical industry to get the production chain rolling. Unlike South Korea, they no longer needed to independently develop one. A test formula was now publicly available. Second, the WHO began to manufacture test kits to send out to other nations who requested them. These manufactured kits provided physical samples of the published testing formula — making it easier for manufacturers in other countries to validate and reproduce. Third, WHO served as an agency that mass produced tests. This helped to provide tests to those who were unable to provide for themselves. By March 16, two months later, WHO alone had produced 1,500,000 tests and sent kits out to 120 countries.

The gene assay of SARS-CoV provided by Olfert Landt to the World Health Organization in January. This assay would result in an easily producible test that many nations would use to contain their COVID-19 outbreak. Image source: WHO.

Independently, the German firm that provided the first test protocol adopted by WHO was also shipping out tests to other countries. In mid-January, New Zealand, who decided the WHO-published test formula was good enough and the need for more immediate access to tests was greater than the need to independently produce one at home, ordered the Germany-developed kits. The kits were subsequently shipped. And New Zealand was provided with tests ahead of the outbreak that later occurred. In other words — they were prepared. Australia and a number of other countries made the same decision — also ordering their test kits from overseas. Olfert Landt’s firm, the German Agency that developed the first COVID-19 test protocol adopted by WHO, alone was shipping out 1,500,000 tests per week by late February of 2020.

U.S. — All Testing Eggs Slow-Walked into one Trump-Shrunken Basket

In the U.S., the Centers for Disease Control, a crucial public health protection organ, had long suffered budget cuts and diminishment under Trump. As noted before, each of Trump’s budgets had requested reduced funding for CDC and his attacks on the Affordable Care Act also degraded U.S. disease fighting capability. His removal of Obama’s Pandemic Task Force had cut off a federal limb that could have helped stop the virus in its tracks overseas, but if it did get out could have also coordinated infectious disease response at home and abroad, cut red tape, and sped the availability of materials such as test kits for the U.S. public.

Perhaps as equally pivotal, though, was Trump’s choice of director — Robert Redfield — to head CDC. Redfield, unlike many of Trump’s appointees, was certainly a professional with many years of experience in his field. One who spent 30 years researching HIV and for 20 years served in the U.S. Army Medical Corps. Redfield was, arguably though, far from a great choice to head the agency responsible for fighting disease in the U.S. He was embroiled in a controversy over an HIV vaccination trial in the 1990s in which he was accused of manipulating data. Redfield has also been criticized for allowing his strong religious beliefs to interfere with his medical views. Peter Lurie from the Center for Science in the Public Interest, a consumer advocacy group expressed this concern about Redfield’s appointment: “What one would get in Robert Redfield is a sloppy scientist with a long history of scientific misconduct and an extreme religious agenda.”

In choosing the controversial Redfield, Trump also passed over Anne Schuchat — a career public servant whose experience dealing with Anthrax in the U.S., Ebola in West Africa, and SARS in China made her an ideal choice for CDC head. In other words, an infectious disease expert with exactly the kind of experience to handle an illness like COVID-19. That’s what the people of the United States didn’t get from Trump. What we got was something that we’ve come to expect from a corrupt and incompetent Administration — at best a political appointee with professional credentials but also possessed of a questionable and often partisan-charged past, at worst the same but with no professional standing whatsoever.

As it happened, on the same day that WHO had published Olfert Landt’s test kit formula on its website, January 17, a sapped CDC in the U.S. announced that it had developed its own preliminary test for COVID-19. They’d decided to work on their own test. This decision was guided in part by regulation — and much of it for good reason. We didn’t want to open the door to fraudulent tests. But it was also a decision that occurred in the context of a global health emergency. And leadership from the top could have worked to ensure the protective needs of regulation were adhered to while still providing back-up options if the CDC-sponsored test kit development occurred too slowly or didn’t produce a usable test soon enough.

In other words, they could have cut red tape to enable medical industry in the U.S. to produce coordinate tests. Like South Korea, they could have called together industry heads and provided organization and guidance. Something a dedicated pandemic response team, had it been in place, could have helped to accomplish. Something a CDC head with novel pandemic chops like Anne Schuchat would have recognized the need for. CDC could have worked to validate those tests in conjunction with its own test. It could have used one of a number of WHO-validated formulas for these coordinate tests. It could have set up teams to work to validate multiple sets of tests to determine which ones were effective. It could have worked to set up contingency surge production if more tests were needed (as happened in South Korea and elsewhere).

The bio of Anne Schuchat — the kind of infectious disease expert that the U.S. is capable of fielding to head an effective pandemic response. The kind of expert the Trump Administration has repeatedly passed over in favor of less effective leaders. Image source: CDC.

Such a layered strategy did not develop at CDC under Redfield as head. At first, and for many weeks after, the decision by leadership was to support one testing regime and then to in a laissez faire way, ignore the fact that other agencies such as FDA ended up using existing regulation to defend it and to (unintentionally) stymie the independent development of effective tests in the U.S. In other words, through lack of response adequate to the threat of COVID-19, Trump’s CDC head put all their testing eggs into one basket.

Making Our Own Unluck

It all could have still worked out. The U.S. could have been lucky. The CDC test could have worked effectively. It could have arrived in time to help stop the virus. It could have arrived in enough numbers to meet the testing need. It could have been targeted to the regions that needed it most. Trump’s Redfield CDC hadn’t increased their likelihood of that success, though. They had greatly increased the opportunity for failure. And given that self-infliction of a worsened set of odds, things did not go well.

Development of the CDC test notably lagged behind the rest of the world. By January 21, the U.S. saw its first confirmed case of COVID-19. It was of a man who’d flown back from Wuhan, China and entered the U.S. on January 15. But it took another week — until January 28th for the CDC to provide its own test kit formula to WHO — 11 days later than Germany, four days later than China, and weeks after South Korea had developed an effective test protocol. Fully two weeks after the virus had arrived on U.S. shores.

It wasn’t until February 5 — fully 19 days after CDC’s first test protocol was announced — that a CDC under Trump had shipped 200 test kits to more than 100 public health labs across the U.S. These tests were enough to test 60,000 – 80,000 people if the kits proved effective. By the same time, WHO had shipped 250,000 tests that had already been validated. Globally, on February 5, confirmed cases had risen to above 28,000. In the U.S., 12 cases had been confirmed with cases springing up Washington State, Illinois, Wisconsin, California, Massachusetts, and Arizona. Given what we know about COVID-19, actual numbers were probably already much greater than these early confirmations indicated.

The virus had arrived on U.S. shores and CDC had scrambled to send out these test kits. But the test deployment would ultimately prove to be seriously problematic. The trouble with these U.S. tests ended up being four-fold. First, that they had not yet (by February 5) been validated and many would later prove useless. Second, there weren’t enough to meet demand. Third, many came too late. And fourth, test kit distribution was not targeted or weighted to the regions of highest need. Why the U.S. CDC response was so much slower and so poorly coordinated compared to those of other nations has not fully been explained. Nor has it been fully explained why many of the tests that CDC ultimately provided would fail. But this failure was arguably a major reason why COVID-19 would break out to such a great extent in the U.S. Why the U.S. would experience the worst first wave outbreak of this novel deadly illness. Because what ultimately happened was a serious failure to contain the illness once it reached our shores. To perform that detection, contacts tracing and isolation that was proving so useful in places like South Korea.

So by early February, CDC had shipped out about 200 test kits to public health labs across the country. Each kit contained enough material to test between 300 to 400 patients. But because kits were evenly distributed, places with much higher populations, places like public health labs in New York City which would later experience a devastating outbreak, only received enough testing material to test between 300-400 patients at that time. That’s 300-400 tests for a public health lab serving a city of 8.4 million souls.

According to a report from Kaiser:

The kits were distributed roughly equally to locales in all 50 states. That decision presaged weeks of chaos, in which the availability of COVID-19 tests seemed oddly out of sync with where testing was needed.

Another problem was that the test kits that were shipped out often proved faulty — lacking critical components that hobbled kits ability to produce results. So from February 5 to mid February — for about ten days or so — public health labs across the country were put in the position where they needed to validate CDC test kits. And, in most cases, the validation of a useful kit did not occur. By mid-February only about six public health labs had access to reliable tests. But the Trump-appointed CDC director Robert Redfield was at the time entrenched, defending those tests. He insisted that CDC had developed a “very accurate test.”

Global distribution of COVID-19 cases on February 20, 2020. Image source: World Health Organization.

At this point the official number of cases stood at 15. But we know that those numbers were growing unchecked. Mainly because the CDC test kits would prove inadequate. On February 24th, U.S. confirmed cases had jumped to 53 and health experts were saying that community spread was happening in the U.S. On the same day, The Association of Public Health Laboratories sent a plea letter to the FDA asking if states could develop their own testing protocols independent of the CDC. In a few days, FDA reversed its previous position of defending CDC tests as a national standard and allowed states to begin producing their own tests. By February 29, after 43 days, the CDC tests had only been used 472 times. An astonishingly small number compared to the 60,000 to 80,000 that the original test kits should have represented. The U.S. confirmed case total stood at 68. But hundreds more people had already been infected by the illness in the U.S. We just didn’t have much of a way to know who or where because the CDC-backed testing regime ended up being so abysmal.

March Explosion

In the race between testing to track the illness and COVID-19’s in-built imperative to grow beyond our control in the U.S., the virus was winning. It had gotten a big head start of about a month and a half.

By early March, as the number of tests in the U.S. was finally starting to expand, in large part due to rapid production of tests within states and independent of the Trump-hobbled CDC, U.S. confirmed case totals were rapidly shooting upwards. On March 7, confirmed U.S. cases had hit 435. Redfield on the same day noted about the CDC tests: “We found that, in some of the states, it didn’t work. We figured out why. I don’t consider that a fault. I consider that doing quality control. I consider that success.”

By the end of March the U.S. COVID-19 case total would be the largest in the world. This would necessitate a nationwide lockdown as containment failed risking hundreds of thousands of deaths. Image source: Worldometers.

In one more week, confirmed cases would multiply nearly sevenfold — hitting 2,770 by March 14. Tests were finally starting to work and be produced in larger numbers. But for the U.S., a new worrying statistic was starting to become evident — the number of positive cases per test was notably high. In total about 1 out of every 4-5 people receiving a test were testing positive. This was due to the fact that the primary location for U.S. testing was hospitals and emergency rooms. The U.S. did not have widespread dedicated test facilities like South Korea. So most people who got a test were already very ill. All of this was an indication that the U.S. barely understood even the tip of the COVID-19 iceberg that the country was slamming up against.

By March 21, the number of COVID-19 cases had again exploded — hitting 24,345 or nearly ten times their number from the prior week. States such as Washington, New York, and California were testing thousands of people per day now. And a disturbing understanding of the U.S. disease curve was starting to emerge. A model produced by the Imperial College in London projected that as many as 2.2 million people in the U.S. could die if the U.S. did not move strongly to mitigate the spread of the virus.

Moving To Mitigation as Virus Outruns Containment in a Big Way

Unlike testing, contacts tracing, and isolation, mitigation involves serious constraints on activity within the impacted regions. In effect it would mean lockdowns or stay at home orders for much of the nation. A kind of freeze placed on society and economies in order to reduce mass loss of life. We say reduce, because the mass casualty event for the U.S. had already gotten well out of the bag. Tens of thousands would already lose their lives as a result. The question now was between tens of thousands and hundreds of thousands or millions along with a smashed U.S. hospital system.

By March 31, U.S. cases had again exploded to nearly 190,000. Even more tragically, already more than 4,000 souls had been lost due to the virus. A Trump Administration that had promised to provide 27 million tests by that time had only seen the U.S. testing 1 million. And a good portion of these tests were provided not by the CDC or the federal government under Trump, they were provided by states who were forced to scramble to fill the yawning vacuum of a failed federal testing, contacts tracing and isolation response.

Most U.S. states now have more than 1,000 COVID-19 cases. Many now have more than 10,000 cases. The U.S. total will likely near 1 million by the end of April. This massive outbreak has forced large scale mitigation in which most states remain under stay at home orders. Image source: CDC.

Now states would have to step in again. This time to provide the mitigation necessary to prevent about 2.2 million deaths across the U.S., California’s Gavin Newsom issued a stay at home order on March 19, New York’s Governor, Andrew Cuomo, made a similar order just a day later on March 20th, Washington State’s order came on March 25th, Maryland’s own stay at home order began on March 30th. By the end of March, fully 42 states had issued a stay at home policy. A policy that would remain in place for many weeks to come. Containment had failed in a dramatic way. Testing still lagged well behind the need. People who wanted tests still couldn’t get them. And as U.S. COVID-19 case numbers climbed toward 1 million in April, testing would continue to lag the need for it in most places.

The result was a full-on move to mitigate COVID-19’s spread. But the failure to provide enough tests would still haunt the U.S. And a new issue with testing would emerge as debates on how to restart a hobbled U.S. economy in the presence of a widespread and terrible virus that had wafted its way into all corners of our nation would again emerge. Sadly, this debate would continue to include a tone of irrational defiance to advice provided by experts and to the larger threat posed by a deadly and as yet incurable illness from the Trump Administration and its political supporters.

(UPDATED)

Up next: It’s Everywhere Now — COVID-19 A Global Viral Wildfire

Posted by robertscribbler on April 20, 2020

https://robertscribbler.wordpress.com/2020/04/20/the-trouble-with-testing-part-1-no-responsibility-at-all/

Effective Containment — How South Korea’s First Coronavirus Wave was Halted

“Testing on its own will not stop the spread of SARS-CoV-2. Testing is part of a strategy. The World Health Organization recommends a combination of measures: rapid diagnosis and immediate isolation of cases, rigorous tracking and precautionary self-isolation of close contacts.” — COVID-19 Epidemic in Switzerland.

“South Korea has emerged as a sign of hope and a model to emulate. The country of 50 million appears to have greatly slowed its epidemic … Behind its success so far has been the most expansive and well-organized testing program in the world…” — Science Magazine.

“We acted like an army.” — Lee Sang-won, an infectious diseases expert at the South Korea Centers for Disease Control in a statement to Reuters.

*****

If U.S. leadership, under Trump, failed to initially prepare for, recognize, respond to, and effectively communicate to the public on the issue of COVID-19, there was a whole new set of failures surrounding the issue of infectious disease containment. Specifically involving the federal provision of enough tests to the public and to various infectious disease and emergency response agencies to stop a rapidly mounting COVID-19 threat. This failure is a part of the larger response failure by Trump and his administration. In particular, this containment failure was so crucial that it deserves a separate mention (next chapter).

But before we dig into the Trump Administration’s specific failure to provide the tests needed to conduct a successful disease outbreak containment, to gain an accurate picture of the disease outbreak during mitigation, or to provide any hope for an effective reopening of the economy following any successful mitigation, it’s helpful to look at the response of a nation that did manage a successful containment of COVID-19’s first wave. For a rapid response by South Korea, primarily through mass production of tests and subsequent contacts tracing and isolation, squashed what could have been a much more substantial first wave outbreak and ultimately managed to greatly limit new daily cases.

Testing and Containment

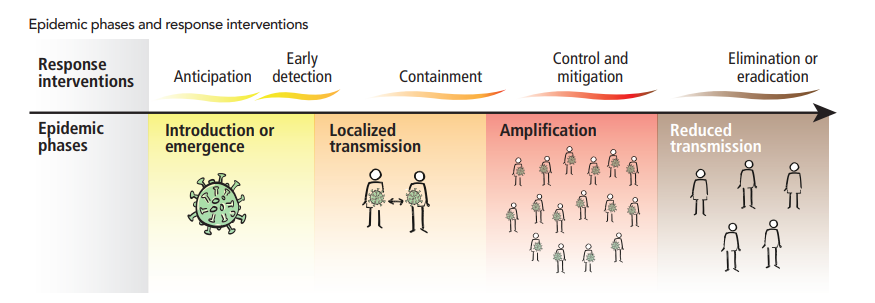

Detection and identification of cases, testing which according to CDC is an essential tool for detecting infectious agents, isolation of confirmed cases, contacts tracing, and isolation of confirmed contacts. In a single sentence, this basically defines a strategy of novel infectious disease outbreak containment (based on CDC’s after action reports on SARS response and CDC’s FAQ on SARS).

Epidemic phases and response interventions. Detection and containment are key responses. Availability of testing is critical for this phase of infectious disease response. Image source: World Health Organization.

It’s used when there’s a new illness outbreak that can’t be effectively treated or cured and when that illness represents a significant threat to life, well being, and a functioning society. In recent years, detection and containment was effective in halting both the first SARS outbreak in 2002 and 2003 and the major Ebola outbreak of 2013-2016. Containment is itself only as effective as the ability to positively identify — often best done through symptoms screening by astute healthcare professionals and testing — a majority of the active cases and to, through contacts tracing, identify each person contacted by the infected individual(s) and to isolate all those involved. If there are not enough tests to measure the number of people infected, if the information management resources do not exist to trace contacts, and if isolation of cases and contacts is not conducted in an effective manner, then containment is unlikely to succeed.

Containment should not be confused with mitigation. But it can be used alongside mitigation as part of a comprehensive strategy of disease response. Mitigation is a strategy to be used either in conjunction with containment of a large outbreak or when containment fails and a widespread outbreak begins to result in disease amplification and/or presents a threat to the effective functioning of healthcare infrastructure. Mitigation often involves social distancing — which is, in effect, the pre-emptive isolation of large sections of society to reduce contacts and to slow disease spread (we’ll talk more about mitigation in a later chapter).

Testing and positively identifying cases enables a second aspect of infectious disease containment — contact tracing. This practice can identify cases quickly and, in conjunction with isolation, prevent illness spread. Image source: CDC and CFCF.

Testing and containment is very important in its own right. It can stop an illness in its tracks. It can save thousands, tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands, or even millions of lives. In the present context of the COVID-19 pandemic, containment has succeeded where testing was widely available and when contacts tracing and isolation was conducted effectively. And in the worst outbreaks — such as in the U.S. — containment failed, in large part, due to lack of the capacity to conduct a large number of tests. This failure resulted in a greater outbreak which froze the economy and required large-scale mitigation to slow disease spread, maintain the ability of hospitals to function, and to reduce loss of life from millions to tens or hundreds of thousands.

South Korea — Learning Hard Lessons From MERS

The story of South Korea’s successful response to the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic begins back in 2015 when MERS was producing a global outbreak of new infectious illness. MERS was another novel disease similar to SARS in that it impacted the human respiratory system and resulted in high death rates. It emerged from yet another climatologically hot region — the Middle East. And MERS was still another novel coronavirus. One also with an ultimate origin in bats. However, MERS is thought to have a zoonosis due to harmful interactions between humans and camels. How MERS spread to camels from bats and then to humans remains somewhat unclear. Though it is thought that the consumption of poorly cooked camel meat is a likely vector for transfer of this new illness to human beings.

MERS was far more deadly than SARS — resulting in mortality in about 1/3 of those infected. Its geographic region of origin was the Middle East. And since the time when MERS was first identified in 2012, approximately 2519 individual infections have been reported on a global basis.

A map of MERS transmission and outbreaks. Human outbreak areas shown in red and blue. Note South Korean outbreak in upper right. Image source: WHO.

In 2015, South Korea had its own tough brush with MERS. At the time, a South Korean businessman became ill after a trip to three countries in the Middle East. He sought treatment at three South Korean health facilities before he was diagnosed with MERS and put under isolation. But his contacts over the interim period ultimately resulted in 184 MERS infections within South Korea and 38 deaths. During this period, South Korea conducted a major response effort to contain the horrifying illness. The prospect of a major epidemic sent alarm signals through the country, slowed its economy, and traumatized the public. In response, South Korea produced a, then major, testing, contacts tracing, and isolation response in order to contain the illness. In the end, over 17,000 people were quarantined in an effort that ultimately quashed the outbreak.

Alertness, Training, and an Early Response

Pneumonia-type illnesses appear to have ingrained themselves on the collective consciousness of South Koreans during recent years. The 2015 MERS outbreak was viewed by many as a wake-up call. But the earlier 2002-2003 SARS outbreak and a general understanding of the risks of new coronaviruses appear to have made their cultural mark as well.

Back in December of 2019, according to reports from Reuters, two dozen top infectious disease experts in South Korea conducted a tabletop exercise. The scenario was oddly prophetic — a family becomes infected with a pnemonia-like illness after a trip to China. In the scenario, the new illness could have been a new form of influenza or a coronavirus like MERS or SARS. The exercise left its mark. And the lessons learned from it would be crucial to South Korea’s rapid escalation.

Just one month later, South Korea was organizing a response to an actual coronavirus pandemic emerging from China. And they were about as ready as they would ever be due to a combination of preparation, concern, and apparent luck. On December 30 of 2019, China and WHO collected and analyzed samples of the novel coronavirus and then communicated first findings. And on January 4th, just five days later, South Korea’s infectious disease experts had access to a test methodology to positively identify COVID-19 cases. This was three days before China had genetically identified the new virus, it was five days before Chinese scientists uploaded a copy of SARS-CoV-2’s genome into an international repository. On January 9th they began lab testing for COVID-19.

They’d learned their lesson from MERS — quick response was absolutely necessary. And top experts still had the recent tabletop exercise fresh on their minds. But they still didn’t have a commercial, mass producible, test. The early testing methodology was slow. It could only manage a small number of cases at a time. As the disease began to rapidly expand in China, South Korean infectious disease experts feared they’d need something that was easily replicated on a mass scale.

On January 27th, South Korean infectious disease control personnel had detected just four cases of COVID-19 but they feared an epidemic. And their fears were rational. They’d experienced the explosive growth of MERS just a handful of years earlier and experts were starting to get hints that COVID-19 was a deceptive illness capable of both eluding detection and rapid expansion without widespread testing and isolation. On the same day, South Korean CDC officials summoned 20 heads of the nation’s medical industry. Their goal — turn South Korea’s lab test into a mass-produced, easy to use, diagnostic test. Just one week later, a diagnostic test produced by one of these companies was approved by South Korea’s CDC.

Lee Sang-won, infectious diseases expert at Korea’s Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, noted to Reuters — “We acted like an army.”

From Testing to Containment — South Korea’s Close Call

The problem with containing a disease like COVID-19 is that it is capable of seriously explosive spread. A single person infected with this illness who gets into a tightly packed setting with a large group or that moves rapidly from person-to-person can become what in disease parlance is known as a super-spreader. On February 18, just 11 days after South Korea had approved a commercially mass-producible test for COVID-19, a woman presenting symptoms who would represent South Korea’s 31st official case tested positive.

She was 61 years of age and, like many of us, she was a social person who delighted in her community. Part of her community was a rather large mega-church — the Shincheonji megachurch in Daegu, about 240 kilometers southeast of Seoul. When her contacts were traced it was found that she attended two services — one on February 9th and another on February 16th. At the time, she was already feeling slightly ill. In the church — 500 attendees would sit, tightly packed, through each 2 hour service.

Infection curve for South Korea shows a major spike in cases during late February and early March, then a rapid flattening that experts attribute to mass testing and isolation enabled by widely available tests for people with symptoms. Image Source: Worldometers.

From February 17 through 29, South Korea experienced an explosion of cases jumping from 31 to 3150. The vast majority of these new cases came from members of the Shincheonji megachurch. At this point, South Korea’s outbreak was the largest outside of mainland China. It was an outbreak that threatened to overwhelm the nation of 51 million people. South Korea’s 130 disease detectives were initially swamped by the Shincheonij-centered outbreak. More than 80 percent of patients with respiratory symptoms from this single outbreak were testing positive and the resources of South Korea’s traditional CDC response force was chiefly focused on this one cluster.

South Korea’s disease response teams were reeling. And without the earlier prep-work, they would have surely failed. As it was, South Korea just barely responded in time to prevent a much larger outbreak.

Responsible Governance Leads to Disease-Fighting Success

South Korea’s fast-tracked testing, contacts tracing and isolation system arrived in late February and rapidly expanded into March. This fast-tracking provided a key new disease response capability exactly when it was needed. By the end of February, just as its outbreak was ramping up, widespread road-side testing centers were opened. These centers were specifically set up to manage infected persons. Staff had personal protective equipment (PPE). They’d been trained in proper infection containment and sanitation protocols. And, in total, these centers were capable of testing thousands of people each day.

One of South Korea’s many drive-through testing centers. At this location, healthcare professionals wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) administer a COVID-19 test. Image source: Government of South Korea.

In addition, specialized government isolation centers were opened for persons infected with COVID-19 — adding an outside capacity that reduced stress to hospitals. People who tested positive were required to download an app on their phone that traced their past movements and contacts. These contacts were also required to download the phone app and to self-isolate. Violators of the self-isolation policy were fined a 2,500 dollar equivalent.

This larger second line of defense enabled South Korea’s health officials to capture cases and conduct larger isolation outside of the initial disease cluster. A massive public health defense infrastructure that effectively sprang up overnight in response to the illness. One that ultimately prevented larger spread, wider sickness, increased illness amplification and death, and a need for even larger resource allocation to fight the disease. A national resource that would prove crucial.

Looking at South Korea’s infection curve, you can see how effective South Korea’s policy of rapid response containment has been. The results speak for themselves. They should count themselves fortunate for the responsiveness and responsibility displayed by their national government and leading healthcare professionals. Their first wave infection curve would have been much worse without it. It could have looked like Italy, or worse, the United States.

(UPDATED — Clarification on South Korea research testing timeline vs China’s COVID-19 research and coordination with WHO.)

Up Next: The Trouble With Testing Part 1 — “No Responsibility at All”

Posted by robertscribbler on April 14, 2020

https://robertscribbler.wordpress.com/2020/04/14/effective-containment-how-south-koreas-first-coronavirus-wave-was-halted/

Denial, Defunding, Downplaying — First COVID-19 Leadership Failures

“Decades of climate denial now appear to have paved the way for denial of Covid-19 by many on the right, according to experts on climate politics.” — Inside Climate News.

“The Democrats are politicizing the coronavirus… and this is their new hoax.” — Donald Trump.

“Just left the Administration briefing on Coronavirus. Bottom line: they aren’t taking this seriously enough. Notably, no request for ANY emergency funding, which is a big mistake. Local health systems need supplies, training, screening staff etc. And they need it now.” — Democratic Senator Chris Murphy

“Now, I want to tell you the truth about the coronavirus … Yeah, I’m dead right on this. The coronavirus is the common cold, folks.” — Rush Limbaugh

“It’s going to disappear. One day, it’s like a miracle, it will disappear.” — Donald Trump

“President Donald Trump has repeatedly undermined science-based policy as well as research that protects public health.” — the Environmental Data and Governance Initiative.

*****

In the ancient story, the prophet goes to confront the king. The prophet says — the Babylonians are coming, we must prepare, we must try to save our people. And the king says — I don’t believe it.

This is tragic. But it is also a dramatic failure of leadership and of a leader’s basic responsibility to protect those she or he serves. Because the point where disaster becomes inevitable is not when news of danger arrives. The point where disaster becomes inevitable, in the face of great danger, is when leadership sabotages itself and everything that relies on it. In the ancient story, the king’s denial is the death-knell for his civilization.

Science Denial As Climate Crisis Enabler

In America, we’ve done our best to remove ourselves from the curse of kings and their blind, cowardly, selfish pride that can hurt so many. But we are not immune to it. Far from it, with the political right now enamored with a novel authoritarianism, we are intensely vulnerable at this moment in history.

It is a vulnerability that we have seen play out again and again in the context of the climate crisis. With Inhoffe’s snowball in Congress, with Trump calling climate change a Chinese hoax during the 2016 election, with the thousands of false climate messages sent out by organizations like the Heartland Institute, with the ongoing attacks on climate scientists coming from platforms like Fox News, right-wing talk radio, and social media.

Even worse, we’ve seen this vulnerability of playing to unfettered and corrupt authority mutate into the climate crisis denial policies — huge subsidies for fossil fuels, erosion or removal of pollution controls, removing clean vehicle standards, hobbling or delaying clean energy systems like wind, solar, and EVs, smearing helpful policies like the Green New Deal, misinforming the public on the efficacy of climate solutions, attacking IPCC findings even while working to water down IPCC messaging, and attacking helpful global climate policies like Paris from every angle imaginable. In this way, a politics of denial becomes a platform both for harmful policy and for harmful behavior.

Anti-Science Denial Becomes Bludgeon

A new vulnerability emerged with COVID-19. A kind of right wing systemic weakness resulting from years of failure to listen to experts and to support the institutions that protect both those of us in the U.S. and people around the world from the ravages of a wave of emerging and re-emerging infectious illness. This vulnerability became visible as China was grappling with a monstrous outbreak during December of 2019 and January of 2020. It became still more apparent during February as COVID-19 threatened to go global, to strike deeply into the U.S. population as well. And by March the various failures of the Trump Administration would result in the U.S. suffering the worst of any nation from COVID-19’s global first wave.

But the failures of leadership that paved the way for COVID-19 to rapidly expand began months and years before. It began with anti-science and anti-public-health Trump-lackey-type Republicans taking control of the executive branch of the United States.

Sabotaging Global and US Pandemic Preparedness

The story of the Trump Administration’s erosion and removal of key U.S. and global protections in the time before the Coronavirus outbreak is extensive. We will touch on some of its highlights here. In short, the removal of protections was deep, it was systemic, and it arose from both the Administration and its supporters’ operating ideology which included actively eroding national and global institutions. It also centered on Trump himself — who seemed unwilling to listen to even his own followers, taking any seeming or perceived contradiction as an insult. Moreover, presented with facts, Trump has repeatedly seemed to consider them an affront to him personally. In this case, Trump and his loyal and unquestioning followers targeted the very institutions aimed at keeping our populations well.

2018 was the first fiscal year budget request by the Trump Administration. This graph by Kaiser is one indicator of how much Global Health was de-prioritized in the transition from Obama to Trump. Image source: Kaiser.

According to reports from Foreign Policy, in 2018 the Trump Administration fired the government’s entire pandemic response chain of command. This included the management infrastructure for pandemics within the White House. An observation that has been broadly validated.

In 2018, the Trump Administration also sought deep cuts in a program called the Global Health Security Agenda (GSHA). The program was aimed at shoring up other countries ability to detect pathogens. The GHSA aimed to set up a global early warning system for new outbreaks of infectious diseases.

In July of 2019, the Trump Administration told an infectious disease expert then in China whose job it was to assist Chinese disease response and to facilitate information sharing between the U.S. and China during a disease outbreak that her job was defunded. This caused her to leave her post. Overall, the Trump Administration dramatically reduced disease response capability in China. According to The Guardian, 11 CDC staffers charged with disease response were cut to three people, while 39 workers who supported them were reduced to 11 people.

In addition, Trump Admin budget requests have asked for a reduction in CDC funding by 15-20 percent for each of the past years. Coordinately, Trump’s attempts to defund the Affordable Care Act would have reduced CDC funding by a further 8 percent. Congress (primarily due to the efforts of Democrats) ultimately restored funding removed in Trump’s budgets. So these cuts did not fully occur. That said, the attempted cuts show the Trump Administration’s preference for disease preparedness erosion. In the end, Trump leadership was still corrosive to the CDC. According to a report provided by the Environmental Data and Governance Initiative:

“President Donald Trump has repeatedly undermined science-based policy as well as research that protects public health. That undermining has eroded our government’s capacity to respond to the coronavirus — from the White House itself to the labs and offices of the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), the federal government’s lead agency for science-based public health. The Trump administration’s widely-reported disbanding of the National Security Council’s directorate charged with global health has, according to many experts, hobbled the United States’ efforts against this pandemic.”

It was a hobbling that not only made the U.S. less prepared, it also set the global field — allowing any new epidemic outbreak to proceed undetected longer, to expand more rapidly into epidemics due to lack of disease response personnel, it disrupted global communications on the issue of illness, and it cost us dearly in both needed response time and lives of those who would not have been infected otherwise.

Ignoring the Severity of the Threat and Confusing the Public

The Trump Administration’s adversarial relationship with the front line soldiers in the global war on infectious disease early-on quickly morphed to a brazen denial of both the threat posed by the disease itself and the need for a strong response once it did emerge.

The timeline for these initial response failures — both a failure to take the threat of the virus seriously and communicate that seriousness to the public and the failure to provide adequate testing (next two chapters), contacts tracing, containment and isolation early on — occurred during January, February, and early to mid-March of 2020 as the disease first mostly ravaged China, then appeared overseas at first in large numbers in places like South Korea (high case numbers were, in part, due to an aggressive testing regime resulting in a clearer outbreak picture there) and then Iran with small numbers of cases elsewhere. By the end of February, it was clear that Italy was seeing uncontrolled spread of COVID-19 as well (with around 2,000 reported cases at the time). And by early-to-mid March it was apparent that both the US and large swaths of Europe were in the same boat.

Painting False Comparisons with Seasonal Flu and “Moving to Zero” in a Few Days — Trump’s Long March of Misstatement

Trump’s downplaying statements began in January and continued on through mid-March. On January 22nd, Trump stated to CNBC “We have it totally under control, It’s one person coming in from China, and we have it under control. It’s going to be just fine.” This initial major statement came notably late — weeks after first warnings (December 31) from China and WHO, and five days after CDC, in an almost unprecedented move, sent 100 disease screeners to U.S. airports. Trump’s statement was also apparently contradictory to CDC’s own statement on January 21st in which Dr. Nancy Messonnier noted “We do expect additional cases in the United States and globally.”

On January 23rd, CDC advisers reported to CNN that they were concerned that China hadn’t released enough basic epidemiological data about the virus. The next day, Trump apparently contradicts CDC again tweeting his praise for the Chinese government’s transparency and saying “China has been working very hard to contain the Coronavirus. The United States greatly appreciates their efforts and transparency. It will all work out well…” By the next day, on January 25, there are 1,000 global confirmed cases of COVID-19. By the 26th of January, China reported that the disease can infect people and be contagious before displaying symptoms.

On January 30, 7 cases have been confirmed in the United States but the country is starting to show its woeful lack of testing capability (more on this later), the World Health Organization declared a public health emergency of international concern, the U.S. State Department issued a ‘do not travel’ warning for China. Trump states on the same day: “We think we have it very well under control. We have very little problem in this country at this moment — five — and those people are all recuperating successfully.” This under-counted the official number and stood in contradiction to WHO and U.S. State Department warnings. On January 31, Trump barred many travelers from China. The Administration will later hold up this single, disorganized, inadequate by itself, and too late in retrospect action, as a ‘strong response.’ According to the New York Times, more than 430,000 Chinese still made it to the U.S. despite Trump’s travel ban (40,000 of which arriving after the ban was instated). Trump would later try to turn the blame for the virus onto the Chinese people, in statements that many described as race-baiting and which were reported to have set off a wave of acts of violence against Asian people living in the U.S.

By February 6, the virus was rapidly spreading with 25,000 known cases worldwide. In the following days, Trump would show stunning, and unfounded, optimism stating on February 7 that China will be successful in fighting the virus “especially as the weather starts to warm & the virus hopefully becomes weaker, and then gone.” Infectious disease experts on the same day noted that there wasn’t yet any evidence that warmer weather would slow the virus. On February 10 and 12, Trump would repeat this unproven information stating: “looks like, by April, you know, in theory, when it gets a little warmer, it miraculously goes away.” And “as I mentioned, by April or during the month of April, the heat, generally speaking, kills this kind of virus.”

Local counties, city and state governments, were often forced to contradict myths spread directly from Trump about COVID-19 as a matter of public health and a life-saving measure. Image source: McLean County Health Department.

By February 19, the WHO was now tracking more than 75,000 confirmed cases globally. By February 24, the White House was requesting 2.5 billion in emergency aid funding due to COVID-19. At this point, there were 51 confirmed cases in the U.S. But actual cases were probably far more extensive as U.S. testing capability remained well behind the infection curve. Trump’s statement on this day was also rosy despite a very grim global and U.S. picture starting to emerge: “The Coronavirus is very much under control in the USA. We are in contact with everyone and all relevant countries. CDC & World Health have been working hard and very smart. Stock Market starting to look very good to me!” It’s also at this point that Trump began his counter-productive increased obsession over the stock market. On February 25, CDC again showed how out of touch Trump was with reality on the ground by stating that it expected to see both community spread and thousands of deaths in the U.S.

By February 26, Trump seemed bound and determined to overwhelm the dutiful reporting of infectious disease experts with utter nonsense. He made an odd comparison between COVID-19 and the flu and then he claimed that U.S. cases would be down to zero in a couple of days. For the sake of accuracy, infectious disease experts estimated COVID-19 lethality to be 10-40 times worse than the seasonal flu (as of this writing the disease has killed more than 100,000 people globally, more than 18,000 in the U.S., is the leading cause of death today in the U.S., and has a present global case fatality rate of around 6 percent or 60 times worse than typical flu). It’s also worth noting that at a time when the official CDC case count was 58, Trump falsely claimed the number was 15. Trump’s full statement is worth reading as an example of how delusional the deniers of scientific fact can become and how damaging such delusion is to our lives: “I want you to understand something that shocked me when I saw it that — and I spoke with Dr. Fauci on this, and I was really amazed, and I think most people are amazed to hear it: The flu, in our country, kills from 25,000 people to 69,000 people a year. That was shocking to me. And, so far, if you look at what we have with the 15 people and their recovery, one is — one is pretty sick but hopefully will recover, but the others are in great shape. But think of that: 25,000 to 69,000. … And again, when you have 15 people, and the 15 within a couple of days is going to be down to close to zero, that’s a pretty good job we’ve done.”

The next day, on February 27, there were 60 confirmed U.S. cases of COVID-19. Trump at this time was still living in the cloud of his self induced denial euphoria. His statement for the day was: “It’s going to disappear. One day it’s like a miracle, it will disappear.” On February 29 the refrain for Trump continued at the Conservative Political Action Conference in Maryland when he stated: “And we’ve done a great job… Everything is really under control.” Later it was confirmed that an attendee at the same conference tested positive for COVID-19. On the same day, health officials announced the first official COVID-19 death in the U.S. Later on the 29th, Trump would claim that: “we have far fewer cases of the disease then even countries with much less travel or a much smaller population.” Of course this statement would later be proven dramatically false as U.S. cases jumped to highest in the world on a numerical basis (as of this writing, U.S. cases are now rapidly closing in on half a million).

By early March, cases were notably surging in the U.S., but testing capability still lagged, so only the most severe or high profile infections were accounted for. Regardless, on March 4, 217 cases were confirmed in the U.S. On the same day, Trump was telling people: “Yeah, I think where these people are flying, it’s safe to fly. And large portions of the world are very safe to fly. So we don’t want to say anything other than that.” At this point such statements were directly risking life — it was like telling people to go to the beach in a category 5 hurricane. Conservative followers of Trump would make similar irresponsible statements risking harm to those who listened to them in the weeks and months to follow. It’s also worth noting that the coronavirus denial messages had extended to Trump’s flu comparison by this time as well. A poll conducted by Vox from mid-March found that 90 percent of Fox viewers felt it was safe to go out even as experts were increasingly recommending stay at home policies. But looking at this litany of Trump statements, it’s little wonder how many developed such a false sense of security.

To round out this account of live-action denial, on March 6 Trump began to downplay the lack of testing availability claiming: “Anybody that wants a test can get a test. … The tests are all perfect, like the letter was perfect, the transcription was perfect, right?” This as many Americans with symptoms were forced to wait in long lines only to be turned away when asking for a test. And by March 9, Trump is again making the false equivalency comparison with the seasonal flu: “So last year 37,000 Americans died from the common flu. It averages between 27,000 and 70,000 per year. Nothing is shut down, life & the economy go on. At this moment there are 546 confirmed cases of CoronaVirus, with 22 deaths. Think about that!”

We’ll pick up the thread of Trump misstatement in a later chapter. For now, we will mercifully break from his ongoing and delusional screed to take a look at how the Administration failed so miserably to provide the much-needed test kits that could have helped to contain COVID-19 in the U.S. even as the disease rapidly spread. To look at what could have been and to try to learn from the successful responses of other nations.

(UPDATED to include more information on Trump’s China travel ban in late January.)

Up Next: Effective Containment — How South Korea’s First Coronavirus Wave was Halted

Posted by robertscribbler on April 10, 2020

https://robertscribbler.wordpress.com/2020/04/10/denial-defunding-downplaying-first-covid-19-leadership-failures/

COVID-19 First Outbreak — Viral Glass-Like Nodules in Lungs

“The chances of a global pandemic are growing and we are all dangerously underprepared.” — World Health Organization in a September 18, 2019 statement mere months before the COVID-19 outbreak.

“There’s a glaring hole in President Trump’s budget proposal for 2019, global health researchers say. A U.S. program to help other countries beef up their ability to detect pathogens around the world will lose a significant portion of its funding.” — From a 2018 NPR news report.

*****

During recent years the world has swelled with new and re-emerging infectious illnesses. Ebola, HIV, and SARS were among the worst. And many were accelerated, worsened or enabled through various harmful interactions with the living world to include deforestation, the bush meat trade and the climate crisis. But these illnesses were not the only ones. Between 2011 and 2018, the World Health Organization had tracked 1,483 epidemics worldwide including SARS and Ebola. These illnesses had forced human migration, lost jobs, increased mortality, and major disruption to the regions impacted. In total 53 billion dollars in epidemic related damages were reported.

Comparison of lungs of a Wuhan patient who survived COVID-19 — image A-C — to those of a patient who suffered death from the illness — image D-F. Both image sets show the tell-tale ground glass like opacities of COVID-19 in lungs. Image source: Association of Radiologic Findings.

By late 2019, before the present pandemic, a sense of unease had appeared to settle upon the global health, threat analysis, and infectious disease response community. The Global Preparedness Monitoring Board (GPMB) convened a joint World Bank and WHO meeting during September. The meeting brought with it a kind of air of dread. At the time, various climate change related crises were raging around the world and the general sense was that the human system had become far more fragile in the face of an increasingly perturbed natural world. At the conference, members spoke uneasily about past major disease outbreaks like the 1918 influenza pandemic that killed 50 million people. About how we were vulnerable to that kind of potential outbreak in the present day.

“While disease has always been part of the human experience, a combination of global trends, including insecurity and extreme weather, has heightened the risk… The world is not prepared,” GPMB members warned. “For too long, we have allowed a cycle of panic and neglect when it comes to pandemics: we ramp up efforts when there is a serious threat, then quickly forget about them when the threat subsides. It is well past time to act.”

And they had reason to be uneasy, for even as global illnesses were on the rise in the larger setting of a world wracked by rising climate crisis, reactionary political forces in key nations such as the United States had rolled back disease monitoring and response capabilities. It basically amounted to a withdrawal from the field of battle against illness at a time when those particular threats were rising and multiplying. And the responding statements of increasingly loud concern coming from health experts and scientists, ignored or even muzzled by the brutally reactionary Trump Administration, would end up being devastatingly prophetic.

Live Animal Markets Again Suspect

“We do not know the exact source of the current outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The first infections were linked to a live animal market, but the virus is now primarily spreading from person to person.” — CDC.

*****

If the story of how SARS first broke out in 2002-2003 is not fully understood, then we know even less today about how the second strain of SARS (SARS-CoV-2 or COVID-19) made its way into the human population. What we do know is that the disease is closely associated to a coronavirus found in bats, that the disease transferred from bats or animals ecologically associated with bats and the virus (such as pangolins or civets) to humans through some vector, and that live animal markets remain high on the suspect list. According to recent scientific reports, an intermediate host such as a pangolin, a civet, a ferret, or some other animal like the ones sold in wet markets probably played a role. Chinese health experts also identified a seafood and wildlife market in Wuhan as the original source of the new illness in January.

Regardless of its zoonotic genesis, COVID-19 made its leap into the human population sometime during late November or early December of 2019 in Wuhan, China where it began to spread. At first the spread was relatively slow. Or it seemed slow, due to the fact that the initial source of the infection was small — possibly just one person. But viral spread operates on an exponentiation expansion function. And like its cousin SARS-CoV, COVID-19 was quite transmissible — generating about 2.2 persons infected for each additional new illness.

Wuhan Suffers First Outbreak

At the time, no-one really knew how rapidly the illness spread. Some early reports of the disease seemed to indicate that it was easy to contain. That it wasn’t very transmissible. These accounts would prove dramatically wrong in later weeks. But this early confusion about the risk posed by COVID-19 did hint at its nasty, sneaky, back and forth nature. About how it lulled the unprepared and the overconfident into a sense of false security early on. It also would later show that slower responses to the illness in its ramp-up phase would prove devastating.

By December through mid-January, Wuhan was dealing with an uptick in pneumonia-like infections. Having experienced SARS illness before, the region was put on alert after getting days of indicators that all was not right. These response efforts have been criticized as slow. How it happened is also opaque. One reason is that China was rather close-lipped about the outbreak’s rise on its soil at first. But another reason (an arguably much greater one) for this lack of clarity is due to the fact that many U.S. disease monitors charged with providing reports about the infectious disease situation on the ground in China and various other countries were removed by the Trump Administration in the years and months leading up to the outbreak.

Despite not providing a clear early picture of the outbreak, China did start to rapidly and effectively respond during December and January. In December, researchers received samples of the disease which they identified as a new coronavirus infection — naming it SARS-CoV-2. Once samples were available, both China and the World Health Organization (WHO) swiftly and dutifully produced tests to detect the illness. As of late January of 2020, China had 5 tests for COVID-19. At the same time, WHO began deploying tests to countries and by February the global health agency had shipped easily produce-able tests to 57 countries. This early availability of testing capability provided by WHO would prove crucial to the effective infectious disease responses of many countries in the follow-on to China’s disease outbreak.

Viral Glass Like Nodules in Lungs

Back in Wuhan and in larger China, it was becoming apparent both how deadly and how transmissible the new SARS was. From mid January 23 through February 18 — over a mere 26 days — the number of reported cases rocketed from around a hundred to more than 75,000. About ten times the total cases of the first SARS outbreak in 2002-2003. This even as China shut down large regions of the country, putting the whole Wuhan region on lock-down, and setting up dedicated COVID-19 testing and treatment centers. Notably, the new SARS-CoV-2 had become not only a serious threat to China. It was now a significant threat to the globe — one unprecedented in the past 100 years. A threat on a scale that disease experts had warned of during late 2019. One that if it broke out fully was more than capable of mimicking the 1918 flu pandemic’s impact and death tally.

After rapid growth in COVID-19 cases in China, a strong national response has limited the first wave of outbreak in that highly populous country to just over 80,000. Image source: WorldoMeters.

The disease, which had first been seen by some as mild and easy to contain, had taken hold to great and grim effect. It produced direct and serious damage to people’s lungs. China’s dedicated mass testing centers quickly adapted to look for the tell-tale and devastating signature of COVID-19’s progress in the human body. A kind of viral glass like set of nodules that appeared plainly in scans of victims lungs.

As devastating as the disease was to individual bodies, it hit community bodies hard as well, producing mass casualties as about 15 percent of all people infected ended up in the hospital. A large number of these hospitalized cases required intensive care support (ICU) with ventilators and intubation to assist breathing. This put healthcare workers at great risk of infection themselves — because as with SARS — COVID-19 was not containable in the hospital setting without protective gear and masks (PPE). Early indications were that the lethality rate in China was around 2-3 percent or 20 to 30 times worse than the seasonal flu. Present closed reported case mortality for China now stands at 4 percent with 3,333 souls lost.

The progress of COVID-19 in an infected person was itself rather terrifying. Its ‘milder’ expression resulting in severe flu and pneumonia like symptoms with a number of other bodily responses to include serious spikes in blood pressure along with a manic variance in symptom severity. In hospital cases, victims often struggled to breathe to the point that they required oxygen. If the disease progressed, it produced serious inflammation — filling up lungs with fluid requiring support with machines for breathing. Late stage COVID-19 also attacked the body’s organs with inflammation, resulting in a need for multi-organ support in the worst cases.

Massive Outbreak of a Terrifying Illness

It was a nasty, terrible thing. It brought China to its knees — despite what ended up being a strong overall response by the country. At present, China is still recovering, still going slow with certain sectors of its economy despite limiting new cases to less than 100 per day.

The first outbreak in China was extraordinary in number of persons infected. So large as to be extremely difficult to contain through a well managed global response. But the response from key nations like the U.S. was not well managed. So through various contacts and travel vectors within the human system, this serious illness made its way out to the rest of the world. For the diligent contacts tracing and isolation, the early detection and response by international disease experts that had contained Ebola and the first SARS outbreak had been both hobbled and overwhelmed.

Up Next: Denial, Defunding, Downplaying — First COVID-19 Leadership Failures

Posted by robertscribbler on April 8, 2020

https://robertscribbler.wordpress.com/2020/04/08/covid-19-first-outbreak-viral-glass-like-nodules-in-lungs/

The Emergence of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)