Greta Thunberg was arrested in Germany protesting coal mines as fossil fuel burning and El Nino threaten building heat, extreme events.

All posts tagged Global Sea Level Rise

The Girl Hero, The Beast, and The Ocean

Posted by robertscribbler on January 18, 2023

https://robertscribbler.wordpress.com/2023/01/18/the-girl-hero-the-beast-and-the-ocean/

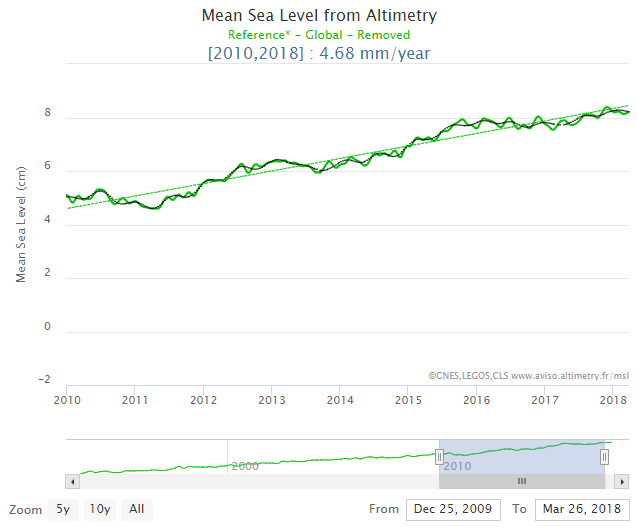

Global Sea Level Rise Accelerated to 4.6 mm Per Year After 2010

Human forced climate change through fossil fuel burning now presents a serious threat to the world’s coastal cities and island nations. Diverse regions of the world are now facing increased inundation at times of high tide and during storms. Unfortunately, this trend is only worsening. And depending on how much additional fossil fuel is burned, we could see between 2 to 10 feet or more of sea level rise this Century.

(Sea level rise analysis and update based on information provided by AVISO, Climate Reanalyzer, and the work of Dr. James Hansen.)

As the Earth has steadily warmed to 1.1 C above 1880s averages, the oceans of our world have risen. At first, the rate of rise was very mild — a mere 0.6 mm per year during the early 20th Century. However, as the rate of global warming increased and the oceans took in more heat, the middle 20th Century saw sea level rise increase to 1.4 mm per year. By the end of the 20th Century, the polar glaciers had begun to melt in earnest. And from 1990 to the present day, the rate of sea level rise has accelerated to 3.3 mm per year.

Due to more warm water invading the basal regions of glaciers and more ice bergs calving into the world ocean, the annual rate at which ocean levels increase continues to jump higher. And during recent years — from 2010 to 2018 — the world ocean has risen by nearly half a centimeter each year (4.6 mm).

(Since 2010, the rate of sea level rise has again accelerated. And it appears that El Nino years have recently tended to produce strong upward swings in the annual rate of increase. This may be due to El Nino’s tendency to set up stronger cycles of energy transfer to the poles. NOAA presently indicates a 50 percent chance that a mild to moderate El Nino will emerge during the winter of 2018-2019. Will we see another sea level spike at that time should El Nino emerge? Image source: AVISO.)

Now both island nationals and coastal cities face the increasing danger of rising tides, of inundation, and of loss of lands and infrastructure. A rapid switch to renewable energy and away from fossil fuel burning is needed to save many regions. However, due to presently high greenhouse gas accumulation, it is likely that some zones will be lost over the coming decades.

Posted by robertscribbler on May 15, 2018

https://robertscribbler.wordpress.com/2018/05/15/global-sea-level-rise-accelerated-to-4-6-mm-per-year-after-2010/

Grim News From NASA: West Antarctica’s Entire Flank Collapsing Toward Southern Ocean, At Least 15 Feet of Sea Level Rise Already Locked-in Worldwide

(Must-watch NASA presentation finding six Antarctic Glaciers in irreversible collapse.)

Human-caused heat forcing. From the top of the atmosphere to the bottom of the world’s oceans, there’s no safe place to put it. For where-ever it goes it sets in place conditions with the potential to unleash gargantuan forces.

481. Minus aerosols, that’s the equivalent CO2 heat forcing humans have now built up in the atmosphere due to a constant and rapidly rising greenhouse gas emission. By itself, this heat forcing, were it to remain in the world’s atmosphere and ocean system, is enough to melt all of West Antarctica, all of Greenland, and part of East Antarctica pushing sea levels higher by between 30 and 120 feet or more.

Inertia. Namely, the massive inertia in the Earth climate system creating a perceived ability to resist rapid destabilization due to the human insult. It’s the one hope scientists and policy-makers alike pinned on the possibility of bringing human greenhouse gas emissions down in time to prevent radical and damaging change.

Rapid glacier and ice sheet destabilization. What, by 2014, became understood as the new reality, as an ever-increasing number of the world’s glaciers displayed far less resilience than previously anticipated and were set in motion to an unstoppable and catastrophic reunion with the world’s oceans by human warming.

Now, a new NASA study finds that six of West Antarctica’s largest glaciers are in a state of irreversible collapse. These add to a growing tally of destabilized glaciers from Greenland to Svalbard to Baffin Island to Antarctica and beyond which, all together, show that at least a 15 foot sea level rise from human-spurred glacial release is now inevitable.

Their names were Pine Island, Thwaites, Haynes, Pope, Smith and Kohler

(The locations of West Antarctica’s ‘butcher board’ glaciers — those that are doomed to an inevitable embrace with the Amundsen Sea. Image source: NASA.)

At issue are six massive glaciers representing more than 1/3 of total the ice mass of West Antarctica and what could well be called its entire weak flank.

As early as 1968, this massive section of West Antarctica was listed as unstable. Since that time, human heat forcing has pumped higher and higher volumes of warmth deep into the Pacific Ocean. The warmth pooled in the depths, building, even as it rose up beneath Antarctica. Ocean circulation and Ekman pumping along the coast of Antarctica brought this warm water up from the depths where it traveled along the continental shelf zone to encounter Antarctica’s mile-high glaciers. The warm water did its work, unseen, for a time. Eating away at the bottoms of these glaciers and speeding their slide to the sea. The increased glacial melt and related fresh water outflow put a kind of cold water cap on the Southern Ocean around Antarctica. This cold cap gave the ever-warming bottom waters no outlet to the surface and so the heat concentrated where it was needed least — at the bases of massive ocean-fronting glaciers.

One section of West Antarctica, composed of the six glaciers now listed as undergoing irreversible collapse, was particularly vulnerable to this basalt melt and ocean upwelling heat forcing. For the glaciers there rested on a section of continental shelf well below sea level — extending scores of miles beneath the ice and on into interior Antarctica. As a result, newly undercut glaciers are flooded until they float, creating lift, reducing friction and rapidly speeding the glacier’s plunge seaward. Even worse, few sub-glacier ridges — speed bumps that glaciologists call grounding points — interrupt the more rapid flow of these glaciers once initiated.

(NASA slide-show illustrating the process of basal melt and grounding line retreat)

By earlier this year, a separate NASA study found that the Pine Island Glacier (PIG), one of the world’s largest glaciers and the most vulnerable ice sheet in West Antarctica, had entered a state of irreversible collapse. Now, the most recent study, led by glaciologist Eric Rignot at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, finds that five of its fellows — Thwaites, Haynes, Pope, Smith, and Kohler — are following PIG’s lead.

Rignot’s findings could not be more stark:

“The collapse of this sector of West Antarctica appears to be unstoppable. The fact that the retreat is happening simultaneously over a large sector suggests it was triggered by a common cause, such as an increase in the amount of ocean heat beneath the floating sections of the glaciers. At this point, the end of this sector appears to be inevitable.”

In other words, over the course of decades-to-centuries, these glaciers will disintegrate and slide into the sea until they are no more. Years from now, their names will be a distant memory, reminders of a faded and far better time.

At Least 15 Feet of Sea Level Rise From Glacial Melt Now Locked-in

This year, the pace of new announcements for massive glaciers undergoing destabilization or irreversible collapse could best be described as terrifying and unprecedented. And each new announcement brings with it starker implications for both the ultimate pace and scope of global sea level rise.

(Current pace of global sea level rise at 3.26 mm per year is likely now set to rapidly accelerate coincident with the rapid acceleration and melt of an ever-increasing number of the world’s glaciers. Image source: AVISO.)

The amount of sea level rise to result from just the loss of the disintegrating section of West Antarctica described in the most recent NASA study amounts to at least four feet. But looking around the world we also find rapid destabilization of more than 13 glaciers encircling all of Greenland with one, the Zacharie Glacier, featuring an ice flow that stretches all the way to the center of the Greenland ice mass. Recent studies also find that the massive glaciers of Baffin Island and the world’s largest ice cap — the Austfonna glacier on Svalbard’s island of Nordaustlandet — are all locked in an inevitable seaward rush.

The total water composed in the moving and destabilized glaciers worldwide is now at least enough to raise world ocean levels by a total of 15 feet. But the inevitable loss of these glaciers tells a darker tale, one that hints that the 23 feet worth of sea level rise in all of Greenland’s ice and the 11-13 feet of sea level rise in all of West Antarctica’s ice may well be locked in to what is a growing daisy chain of explosive destabilization if human greenhouse gas levels aren’t radically drawn down.

In continuing to emit greenhouse gasses, we make the situation ever worse by imposing a heightening heat pressure on glacial systems that will both speed their release and ensure that an ever growing portion of the Earth’s ice ultimately melts. The current forcing though both extreme and dangerous is small compared to the potential forcing should we not rapidly reign in the human emission.

Links:

Must-Read NASA Study Showing Six of West Antarctica’s Glaciers in Irreversible Collapse

NASA Video: Antarctic Collapse Explained

Nature: Human Warming Now Pushing Entire Greenland Ice Sheet into the Ocean

Constant Arctic Heatwave Sends World’s Largest Ice Cap Hurtling Seaward

Doomed Pine Island Glacier Releases Guam-Sized Iceberg into Southern Ocean

Scientists: Warming Ocean, Upwelling to Make an End to Antarctica’s Vast Pine Island Glacier

NASA/UC Study: Warming Ocean Found to Melt Ice Sheets From Below

A Faustian Bargain on the Short Road to Hell: Living in a World at 480 CO2e

Hat tip to Peter Sinclair and Colorado Bob

Posted by robertscribbler on May 13, 2014

https://robertscribbler.wordpress.com/2014/05/13/grim-news-from-nasa-west-antarcticas-entire-flank-collapsing-toward-southern-ocean-at-least-15-feet-of-sea-level-rise-already-locked-in-worldwide/